Walk into a U.S. multiplex in 2026 and you can feel the shift. Anime is no longer a niche import you hunt down in a single art house screening. It is premium-format programming, branded popcorn buckets, and opening-weekend box office muscle. In that world, the old line about anime being “just a commercial for the manga” sounds both outdated and oddly resilient.

For decades, the business logic behind many TV anime was blunt. A publisher and its partners would bankroll an adaptation to lift sales of the original manga, soundtrack, Blu-rays, figures and tie-in goods. In the production committee model, risk gets spread across companies that each want a different payoff: a publisher wants print sales, a label wants streams, a toy company wants product, a broadcaster wants ratings, and a game company wants players. The anime itself becomes the loudest billboard in the ecosystem.

That logic never disappeared. It evolved.

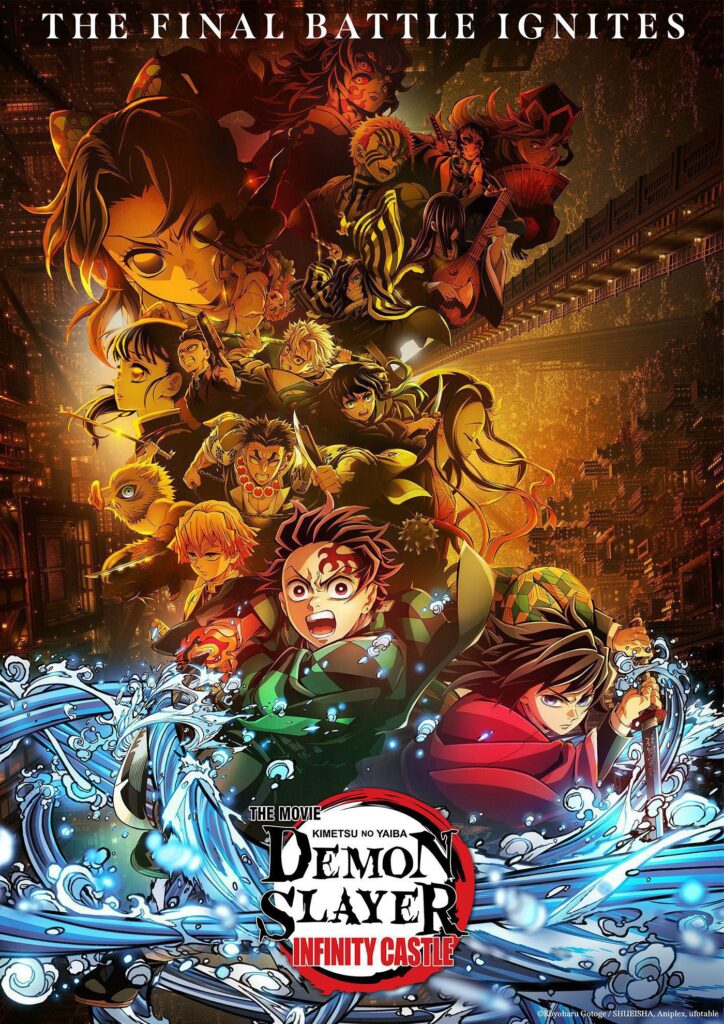

Consider the modern theatrical playbook. “Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba“, already the defining franchise of its era, pushed beyond TV seasons into event cinema, with the “Infinity Castle” film positioned as part of a trilogy and released as a major theatrical title. In North America, the film’s opening was treated like a mainstream box office story, not a fandom footnote. The official marketing is blunt about the strategy: wide releases, premium formats, and urgency, because the series is entering its final battle phase.

Then there is “Chainsaw Man“, a series that carries a different kind of cultural currency: hyper-online, instantly memeable, and built for merch. The franchise moved into theaters with “Chainsaw Man – The Movie: Reze Arc“, rolling out internationally with premium formats and a global distribution push. This is not the old era of a late-night TV slot and a prayer for disc sales. This is engineered as an event.

So, is that still advertising?

Yes, in the most literal sense. Movies sell tickets, sure, but they also sell the idea that you need to be caught up, be part of the moment, and own a piece of it. When a theatrical anime release hits, it triggers the full machine: reprint surges, character goods restocks, collaboration cafes, mobile game banners, and soundtrack drops timed for social media. Even “compilation” theatrical runs, like the recent “JUJUTSU KAISEN The Culling Game Arc“, recap film are explicitly designed to keep audiences engaged between seasons, stitching together episodes to create an in-theater reason to stay invested.

But calling anime “just advertising” starts to miss what anime has become in practice: a primary product with its own artistic prestige and revenue gravity.

Anime now functions like Hollywood IP cinema in one crucial way. The adaptation is not simply a marketing expense. It is a flagship. A studio’s schedule, hiring pipeline, and technical development can hinge on these projects. A successful season or film can reconfigure a studio’s future in a way that a modest sales bump for a manga volume never could. And audiences are no longer treating anime as a middle step to the “real” version. For a growing segment of global viewers, the anime is the definitive text.

That matters because the medium’s creative incentives have shifted. If a show only needs to be good enough to sell manga, it can coast on hype and cliffhangers. If it needs to win subscription retention, global licensing dollars and repeat theater attendance, it has to deliver spectacle and emotional payoff, even for viewers who will never touch the source material.

You can see it in the production values arms race. “Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba” is often cited for making TV look like film, then turning around and making film feel like a cultural holiday. “Chainsaw Man” became a lighting and compositing flex as much as a story. That is not accidental. It is an industry learning, through money and audience behavior, that animation quality is not garnish. It is the hook.

At the same time, the “advertising” critique persists because the assembly line can still show. Many series still stop after one season, not because the story ended, but because the committee got what it wanted: awareness. Viewers recognize the pattern when a show ends on a tease for arcs that never arrive. That frustration is part of why theatrical films are so revealing. They imply commitment, scale and completion, even when they also serve the wider merch economy.

The truth is that anime is now big enough to be two things at once.

It is advertising in the sense that it sits inside a broader commercial ecosystem. The medium is inseparable from the way modern Japanese entertainment is packaged, licensed and merchandised. A hit series is a brand architecture.

But it is also a standalone entertainment product, competing directly with live-action prestige TV and blockbuster film. It has critics. It has awards attention. It has global distribution strategies and box office expectations. It has fans who identify with it the way earlier generations identified with superhero cinema or prime-time dramas.

So perhaps the more useful question is not whether anime is advertising, but whose interests it ultimately serves.

Sometimes it serves the publisher and the merchandise partners, and the story is paced accordingly. Sometimes it serves the studio’s ambition and the director’s voice, and the adaptation becomes a statement piece. Often it serves both, because in 2026, artistic identity and commercial scalability are no longer opposites. They are collaborators, sometimes uneasy ones.

When you buy a ticket to an anime film, you are buying the night out. You are also buying into a pipeline. You are signaling demand for more adaptations, more premium screens, more global rollouts, more “event” treatment. That demand shapes what gets funded next.

Anime is not merely a billboard anymore. But it still carries billboard logic in its DNA.

Whether that is a flaw, a feature, or simply the cost of getting ambitious animation financed at scale is up to the viewer walking out of the theater, deciding what they just paid for.

————

AnimeTV チェーン bringing you the latest anime news direct from Japan ~ anytime! — Your new source of information!

Please note that this article is simply the opinion of Kiran Kane